GDC Gallery: How The Indie Fund Could Change Game Dev Destiny

Like UK studio Introversion’s indie-rallying clarion call at the 2006 Independent Games Festival, the announcement of an indie-led investment strategy — simply called the Indie Fund — could be the next watershed moment for the future of independent gaming. Organized by a consortium of indie devs that’ve seen breakout success (like World of Goo creators 2D Boy and Braid developer Jon Blow), the fund aims to maintain control of the funding cycle — keeping it out of the hands of publishers and traditional investors alike — and keep indies in charge of their own destiny. Opening the 2010 Independent Games Summit, 2D Boy co-founder Ron Carmel took to the stage to explain why the fund was needed, with Braid artist David Hellman illustrating the strange over-complex steamwork behemoth of traditional business models that no longer serve the indies best: the full hi-res gallery continues below.

Like UK studio Introversion’s indie-rallying clarion call at the 2006 Independent Games Festival, the announcement of an indie-led investment strategy — simply called the Indie Fund — could be the next watershed moment for the future of independent gaming. Organized by a consortium of indie devs that’ve seen breakout success (like World of Goo creators 2D Boy and Braid developer Jon Blow), the fund aims to maintain control of the funding cycle — keeping it out of the hands of publishers and traditional investors alike — and keep indies in charge of their own destiny. Opening the 2010 Independent Games Summit, 2D Boy co-founder Ron Carmel took to the stage to explain why the fund was needed, with Braid artist David Hellman illustrating the strange over-complex steamwork behemoth of traditional business models that no longer serve the indies best: the full hi-res gallery continues below.

Adding nuance to

Adding nuance to

the title of his session, Carmel admitted the real problem was

more specific: that the real problem was shoe-horning the new

world of digitally distributed indie games into the old regime

of traditional retail game publishing.  As game development

As game development

has evolved over the past few decades, he explained,

traditional software engineering practices have come with it:

“waterfall approach” processes that emphasize doing as much

pre-production design as possible as early in the process as

possible, postponing the actual building. Throughout the 90s,

though, agile practices emerged that saw development models

being thought of as much more fluid processes, with studies

showing that this model isn’t just cheaper and better for

actually creating software, but maintaining it as well. The

indies are currently facing the same situation today in regards

to funding new games, said Carmel, as the industry still hasn’t

recognized the importance of creating a new mechanism that

takes the new digitally distributed landscape into full

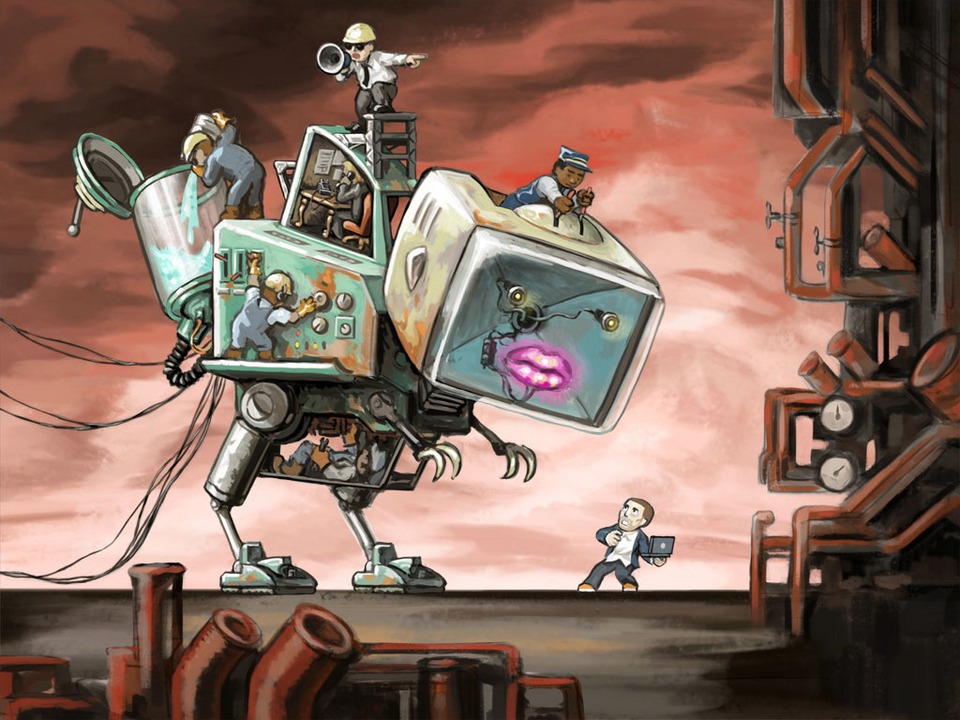

account.  The problems: publishers

The problems: publishers

give too much money for what should be smaller budgets.

World of Goo‘s development costs were in

the region of $120,000, Braid‘s at

$180,000: if publishers are giving out $500,000-$1 million

(presuming old model additional costs of manufacturing and

maintaining inventory, working with retail, marketing), they’re

taking on too much risk and can never hope to make up that

investment. “The machinery for triple-A retail games doesn’t

scale down,” said Carmel — it becomes inefficient and

developers end up becoming tenant farmers. 2D Boy saw this

inefficiency in effect first hand when they approached both

Valve and Microsoft to distribute World of

Goo on both Steam

and Games

for Windows Live. With Games for Windows, each step

of the process had to go through each of the above behemoth’s

component sectors: they’d talk to a business development agent,

which would then move up the chain to managers for approval

before being passed to lawyers, more engineers, platform

specialists, whereas at Steam, the business was handled by one

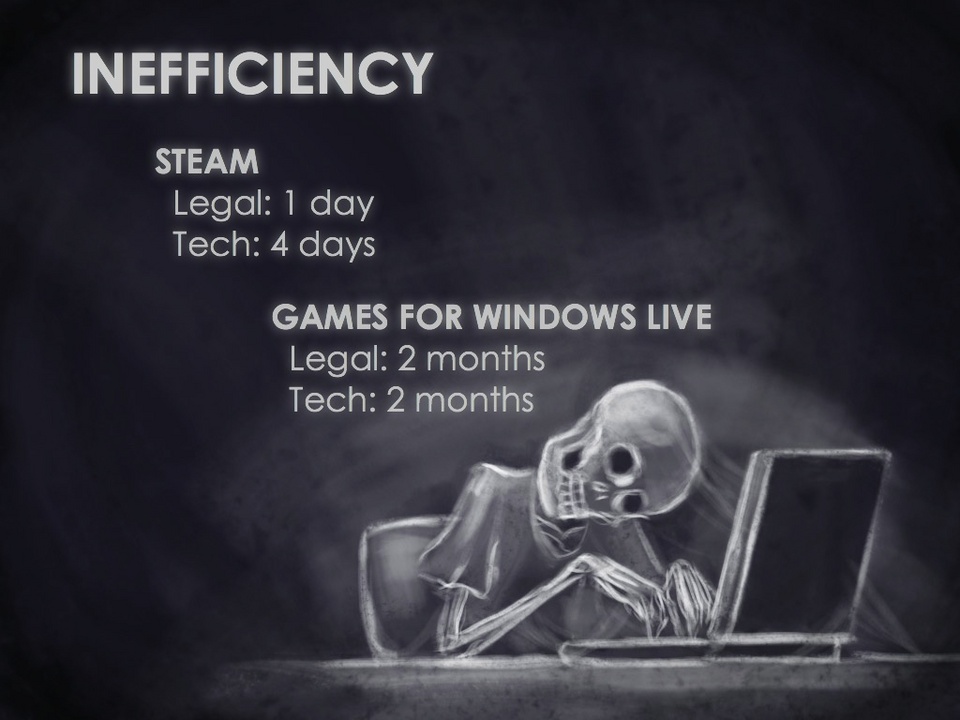

person.  As a result, what

As a result, what

took Valve and 2D Boy one day of legal work and four days of

technical integration on Steam took two months of contract

negotiations and an additional two months of technical work to

prepare the game for launch. It’s not an entirely fair

comparison, Carmel added, with Games for Windows’ inherited

Xbox Live Arcade and retail business model and their newness on

the scene — Steam’s “been around for years” and simply

“figured out how to do this efficiently.” Live Arcade is not

the biggest console distribution platform by accident, he said,

“it takes iterations to get things right.”  But in this new landscape

But in this new landscape

that’s emerged with Steam leading the way to Live Arcade,

PlayStation Network, Direct2Drive, Greenhouse, the developer

and publisher equation has been upended, said Carmel: indies no

longer need the traditional distribution channels publishers

once provided, they simply need the funding. And so, Carmel

said he and the consortium aimed to do for funding what Steam

did for distribution.  And they’d do that

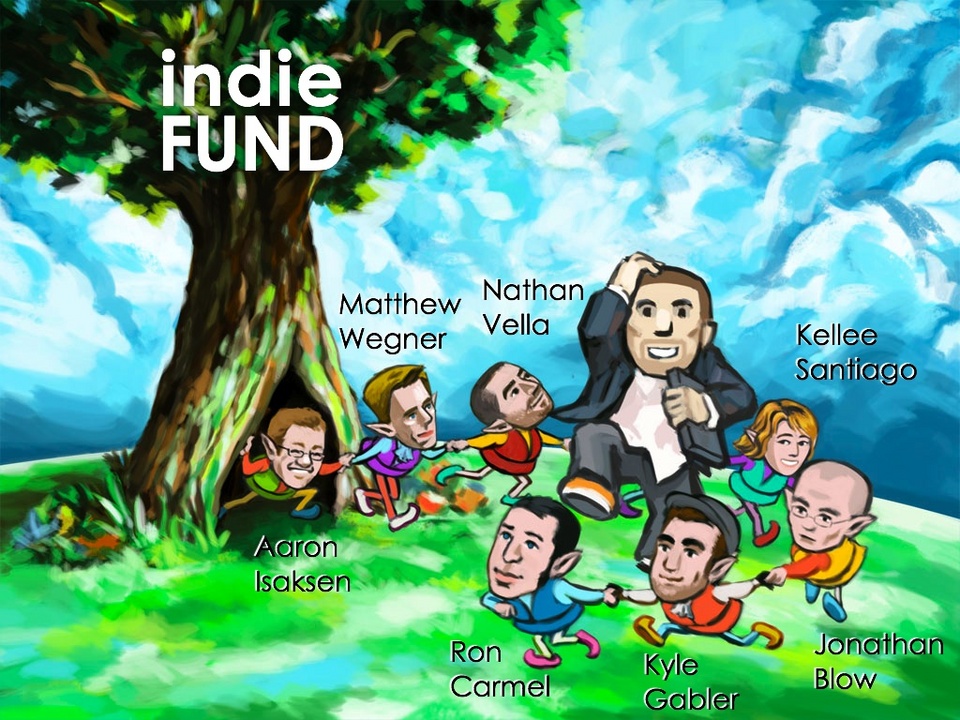

And they’d do that

with the Indie Fund, founded by 2D Boys Ron Carmel and Kyle

Gabler, Braid‘s Jon Blow,

flOwer designer Kellee Santiago, Capy

(Critter Crunch, Clash of Heroes) studio

head Nathan Vella, Flashbang (Offroad Velociraptor

Safari, Minotaur China Shop) co-founder Matthew

Wegner and AppApove (Armadillo Gold Rush)

head Aaron Isaksen. Their goals: to make the submission process

shorter and more transparent, to make terms of funding deals

publicly available (“Developers,” said Carmel, “need to know

when they’re getting good or bad deals”), to maintain Steam’s

single point of contact and personal relationship, to allow

development flexibility and experimentation, and to allow the

developer both the full ownership of their intellectual

property, and no editorial influence over their game (“If we

provide funding, that’s a vote of confidence in the team.”).

When an Indie Fund game ships, Carmel explained, “we recoup our

costs first, and then for limited time get a revenue share from

that game — but that revenue share is going to be much smaller

than what you’d get with a publisher.” The first beneficiaries

of the Indie Fund haven’t yet been revealed, though Carmel

promises we’ll hear more soon — keep checking their

website to contact the team directly or to learn

more.